In 1964, a young Russian-speaking Anglican priest, Michael Bourdeaux, was visiting Moscow when he heard that the Soviet authorities had just demolished a church. He went to investigate and noticed two women peering through a fence at a pile of rubble with a few bent crosses on top.

He approached them and revealed that he was a foreigner wanting to find out what had happened. “We need you,” replied one of the women and asked him to follow them discreetly by tram and bus to a wooden house on the outskirts of the city.

Safely behind closed doors, Bourdeaux explained that his visit had been prompted partly by reading letters smuggled out of the Soviet Union describing brutal attempts to intimidate monks and their congregation at a monastery in Ukraine. “Their faces turned white,” he recalled. “There was a stunned silence, then a cry, muffled in tears: ‘We wrote those documents.’ ”

“What can I do for you?” he asked. “Be our voice and speak for us,” was their reply.

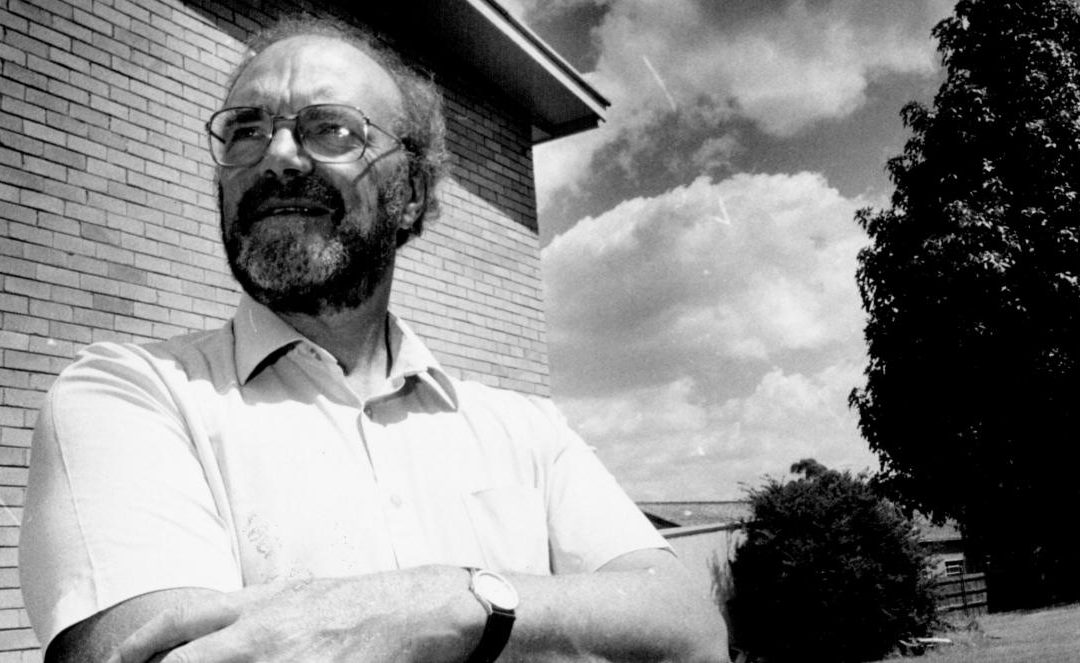

Bourdeaux returned to Britain dedicated to what became his life’s work: researching and publicising what was happening to religious believers in the communist-ruled countries of Europe. “I simply had to speak as a medium for the voice which I had heard so decisively,” he wrote.